This is fairy music, full of playful cross-rhythms and cascading flurries--mercurial delicacy was always one of the specialities of Liszt’s piano-playing. “” robert phillip, The Classical Music Lover’s Companion to Orchestral Music

it is indeed fairy music. though the fairies seem to dance only on the right hand, for on the left--especially in the first, third and fourth movements of this concerto--the pianist is wielding a furious hammer. if not a fairy, then some small caught thing is testing the strength of its barriers, not quite trying to escape nor surrendering to the stillness...perhaps the solo instrument is one such small thing against the tall distance of a cacophonous orchestra: every section seems to be barking a short rehash of the concerto’s nine-note theme that the piano alternatively adopts and resists. of all the concertos in this catalogue, this one feels the most compact and self-contained, thanks to a short and snappy theme that sounds more like the hook to a commercial jingle than the masthead of a concerto four movements long.

The piano enters with double octaves, and embarks on the first of the concerto’s cadenzas. Twice it seems to come to an end, and the orchestra renews its playing of the theme, but each time the cadenza continues. Eventually the piano settles into a rippling pattern, over which a clarinet sings a rising arpeggio. “” robert phillip, The Classical Music Lover’s Companion to Orchestral Music

the unusual format of its movements also contributes to the logical cohesion of the piece: after a brief introductory Allegro, wherein the theme is boldly stated by orchestra, developed in a lengthy cadenza capped by a duet with a clarinet, the next three movements are conjoined without a break in the action. the second movement, Quasi adagio, is in every note unmistakably litzstian. it begins with a fuzzy intro in the cello section--a sketch of gloomy clouds dragging by--down below the piano enters, gentle and hesitant, the left hand strolls along the shoreline while the right hand wades into still waters with uncertain footsteps...

For the theme of the slow movement, Liszt takes a turn of phrase from the first movement’s second theme and extends it into a singing line -- this movement in particular owes much to Chopin, in turn inspired by Italian opera arias. “” robert phillip, The Classical Music Lover’s Companion to Orchestral Music

the same, almost identical, atmosphere is described in the composer’s Consolation No.3 in D Flat Major and is eerily similar to the second movement of rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No.2 written 52 years later. except that the leisure and velleity of rachmaninoff’s Adagio sostenuto is short lived in what liszt aptly named a quasi Adagio--no sooner than the instrument completes its wistful cadenza does the serenity run into strain. the orchestra appears again with the caterwaul variations of that bombastic main theme, a flute interjects briefly with a short solemn phrase but the rabble-rousing returns as the pace quickens towards a shimmering Scherzo.

an ominous jingle on a triangle marks the start of the Scherzo--a more cheerful version of the doleful bells that toll the opening of that aforementioned rachmaninoff concerto--and the third and final movements thereon are bound together in one frivolous leap. a fairly symmetrical dialogue ensues between orchestra and solo instrument as the short quips volleyed by piano are amplified in volume and depth by orchestra. the fourth movement is a fanfare wherein neither piano or orchestra takes the lead in a rapidfire sequence incorporating trombone, timpani and a frothy brass section. beginning as fragments, the main theme returns in exaggerated form, repeated in various tempos until raised in unison as a banner to a triumphant finale.

(program)

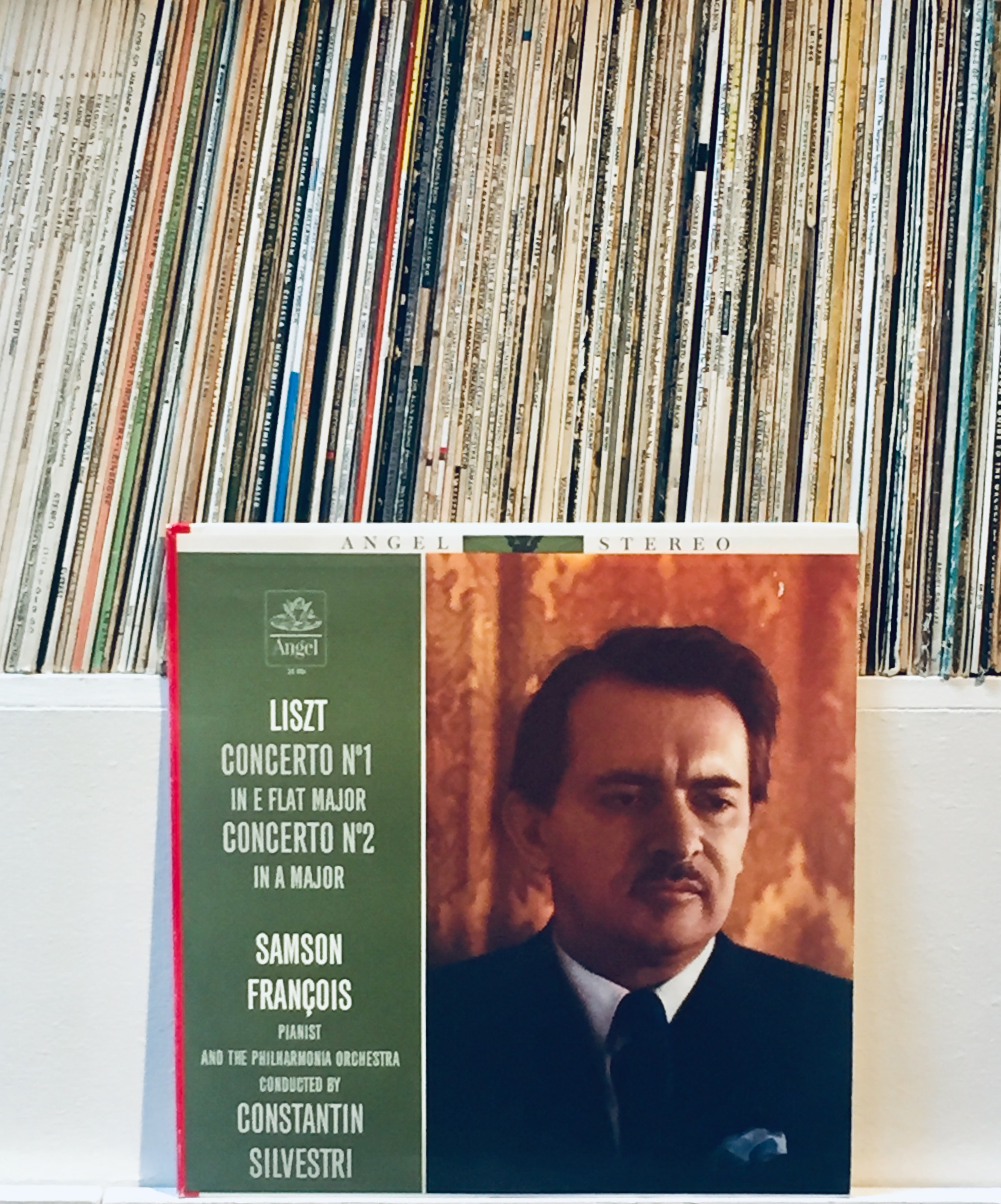

Angel Stereo Recording. Printed in Canada // Franz Liszt (1811-1886) // Piano Concerto No.1 in E Flat Major

The Philharmonia Orchestra, conducted by Constantin Silvestri

Allegro maestoso

Quasi adagio

Allegretto vivace--Allegro animato

Allegro marziale animato

But, whatever one thinks of his grand effects and his fluid structures, Liszt was undoubtedly a great spirit. He had the highest aspirations in his music, he was generous in his support of other composers, and even his failures are impressive Romantic gestures. “” robert phillip, The Classical Music Lover’s Companion to Orchestral Music

(consolation)

the harrowing trailer to british director terence davies’s Of Time and The City, from which i discovered liszt’s Consolation No. 3; it’s one of the most effective trailers for a film i’ve ever seen, and not a single word is said:

(this other little thing i found...)

this week i (finally) finished reading andré alexis’s Pastoral (a title inspired by beethoven’s Symphony No.6) is the first installation in his 5-book series of unconnected novels set in southern ontario. the story unfolds around what barely passes for a main character in Father Pennant, the newly installed priest in the fictional town of Barrow, Ontario; the seemingly mundane--just above the realm of gossip--series of events that unravel upon Pennant’s arrival is alexis’s vector into very some sincere and succinct reflections on the anatomy of love, the supposed limits of Humanism and the eternal project of belonging. last week i was briefly befuddled by a question posed by alexis via the struggles of faith of his Father Pennant, more or less: is Nature enough to satisfy our capacity and desire for wonder?

--So you think the earth is enough?

--No, I don’t. I think there’s plenty we don’t understand, plenty, and if the earth was enough we wouldn’t have to go looking for it. What I think is: there’s enough mystery in this life without dragging incense and holy trinities into it. “” andré alexis, Pastoral

my ‘Yes’ to that is emphatic--in fact moreso this week than the last as a recurrent thought has since crossed my mind: it is exactly the degree to which Nature is in decline that the supernatural is appealing...the bread had to be of especially poor quality to be transubstantiated into ‘body’, and the wine paltry enough to be repurposed as ‘blood’. but an emphatic yes or decisive no are sure ways to ruin an otherwise perfectly readable novel---alexis rises above the bait of such single-mindedness and gives the final words to a priest who, in a moment of clairvoyance, glimpses the possibility that those who have best articulated the supremacy of Nature in our search for wonder--the Enlightenment and the soils of christianity from which grew--have somehow drifted the furthest from the capacity to be in awe of it:

Looking over the land, Christopher Pennant thought of the priests who had preceded him in this country. They had been among the first Europeans to explore Canada. They had come with a mission: to lead the natives to Christianity and salvation. In their single-mindedness, they had done as much harm as good, poor men. They would have done better to learn from those who knew the land. Instead, they had prepared the way for a civilization that had, over the years, turned away from the earth, land and ground. He did not identify with the Jesuits but neither did he identify with any specific tribe. Rather, he envied the ones--whoever they might have been--who’d come through this part of the world when it was virginal. “” andré alexis, Pastoral